Understanding Income Strips

A changed interest rate and inflation environment alongside pension funds’ demand for index linked assets, particularly where they offer diversification, has seen “income strip” finance emerge as a popular option in project finance and for more general capital raising. Yet for many it remains a complex and misunderstood area.

An Introduction

The long lease real estate market has, for decades, created opportunities for investors and asset owners to transact on real estate assets in a way that provides real estate owners with a route to release value from their assets and benefit from certainty of structured long term future rental costs.

Investors, and particularly pension funds, gain access to secure long term cash flows that rise with inflation supported by a high quality underlying credit and offering a premium to more traditional index linked income sources such as gilts and investment grade credit.

While long term sale and leaseback structures and ground rents have traditionally formed the bedrock of long lease real estate, they have not suited all asset owners. However, “income strips” have emerged to offer a further financing route.

Firstly, to clarify the terminology, “income strip” is used to highlight the fact that the investor benefits from income over time. More familiar terminology in finance would be securitisation (of the income) and valuation approaches using discounted cashflows (“DCF”). Interestingly, income strips are most often quoted on a Net Initial Yield (NIY) basis, although they are more typically priced using IRRs, often being a margin over the comparable gilt.

In sale and leaseback, the asset owner sells the freehold and typically signs a fully repairing and insuring (“FRI”) lease with the investor retaining the asset at the end of the lease, in addition to the lease cash flow.

Many asset owners, including local authorities, universities and other similar institutions consider themselves to be ‘forever’ entities. Their time horizons are often longer than other real estate asset owners looking to extract value from their assets through sale and leasebacks. They can be reluctant to ‘sell’ assets, regardless of the leaseback time period. This is where an amortising lease, or income strip offers opportunity: it allows for the sale of the asset, retention of long term occupancy and the right to repurchase the asset from the investor at the end of the lease for a nominal sum (for example, £1). The investor also benefits: the FRI lease term is typically longer, is index linked, and much of the real estate market risk is removed from the investment.

How are income strips structured?

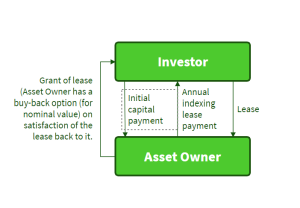

An income strip has similar economics to debt, but is structured and operates in a different way.

Income strips are property transactions based on future lease payments, rather than, say, an indexing annuity based repayment that explicitly includes the repayment of principal and interest. As such they are priced based on a ‘net initial yield’, or NIY. The NIY is a percentage which is the expression of the initial lease payment relative to the upfront capital commitment provided by the investor. The lease payment is then subject to a stated inflation metric, typically applied on an annual basis.

The structuring of the transaction is important. In its simplest form, the original asset owner sells a lease to the investor, who in turn grants further occupational lease back to the original owner. In many circumstances, where these lease payments are met by the original owner over the lease term, at the end of the lease term it has the option to repurchase the lease initially granted to the investor for a nominal amount.

To provide the investor with underlying security, the initial lease granted is typically longer than the subsequent lease back to the initial owner.

The NIY offered typically reflects:

- The investors prevailing view on future inflation this can be based on RPI, CPI, CPI-H, CPI+, or on an LPI basis (where the inflation applied is subject to a cap and/or floor above/below which it cannot increase);

- The timing of the provision of the capital sum and lease payments;

- Underlying asset and the extent to which this affects the credit analysis;

- Investor assessment of the credit quality of the lessor.

- The length of the lease; and

- The investor’s required return based on the above factors, typically with reference to a premium over a risk free return (e.g. a reference gilt yield of corresponding duration).

Asset owners often find it challenging to compare the ‘price’ of an income strip to that of alternative financing, such as fixed rate debt. For example, the NIY cannot be directly compared to an interest rate. QMPF can support clients in considering how they might compare an offered NIY to alternative debt options.

Why have they emerged recently?

QMPF’s experience has been that income strips have become increasingly mainstream over the last 18-24 months (although the first deals of this type occurred in 2010/11), offering relative value for a wider range of projects and asset owners than in the past. As debt pricing has increased in a rising interest rate environment, the corresponding impact on income strips has been less pronounced. This is driven by a number of factors, but particularly that investor focus is on the tenant rather than the asset or project cashflows, and so less constrained by covenant measures such as debt service coverage or gearing. Arguably, as the asset class is better understood and there has been increased competition amongst funders, the required spread over index linked gilts has reduced and illiquidity premium narrowed.

Why might they be relevant to you?

An income strip can offer a direct competitor to debt funding, both for development of new assets and for more general raising of asset secured finance. While investors may prefer that the underlying asset is income generating (e.g. student accommodation) this is not necessarily a requirement. The indexing nature of the payments can offer a different repayment profile, and lower initial debt service cost when compared to fixed rate debt.

Income strip finance is also increasingly being used in the context of project finance transactions, for example funding long term design, build, finance and operate (“DBFO”) contracts with private sector student accommodation providers. While the transaction would be entered into by the special purpose vehicle (“SPV”) providing the DBFO, it is often subject to an underlying ‘Direct Agreement’ with the procuring institution. If the income strip provides a tangible benefit to the project economics (and so a better initial financial outcome for the project procurer) then understanding the implications of the structure for all parties, and its comparison to a more established DBFO funding route, such as bond finance, becomes critical. Key aspects of this comparison will include cost of funds, tenor, amortisation (where applicable), etc.

QMPF’s experience is that there are a number of key considerations beyond relative pricing. These include the detail of the contractual structure proposed and risk transfer achieved, options in the event the DBFO provider underperforms/fails, considerations in relation to the sizing and timing of the funder contribution and comparison of form of the funding documentation (including default/termination liabilities).

What to assess when considering an income strip

QMPF has supported a range of clients in considering and entering into income strip transactions, including within project finance structures. These are not undertaken on a wholly standardised basis and asset owners or procuring institutions need to think through a number of matters when assessing income strip transactions.

QMPF can support you in considering:

- Suitability and your funding requirement: Is the funding requirement and desired funding term aligned to an income strip or would an alternative funding route be more suitable? What does the future debt service profile mean for you?

- Understanding the transaction: The detail of the funding structure, lease structure and contractual structure proposed, as well as aspects including Stamp Duty Land Tax/LBTT and inclusion of “purchaser’s costs” (typical assumptions in a property transaction), need to be fully understood.

- Development period considerations: Income strip financing is a potential route to delivering new developments, but the security package (e.g. development profit reserving) and wider funder requirements may be different from other forms of financing and need to be fully understood.

- Long term asset ownership: How is the asset ownership and reversion managed and what are the associated costs?

- Lease indexation options: What indexation basis best suits your long term objectives? Do you want a cap and/or floor on rent inflation? What is the resulting pricing implication from those choices? Will that preference match funder requirements?

- Relative value: How can you compare an income strip funding route to alternatives?

- Flexibility: Income strip financing is relatively inflexible once agreed, is that fully understood?

- Project structuring: Particularly in a DBFO context, the financing and lease structure, project documentation and funding documentation needs to be developed in a way that balances risk with commercial deliverability.

- Direct Agreement requirements: Within a project finance structure, understanding your obligations under any Direct Agreement is critical.

QMPF can assist you in evaluating funding options available to you. Our Income Strip experience is long standing. Our first income strip transaction with a university was with Swansea in 2011 and we supported University of Brighton to finance a DBFO transaction using an income strip over 5 years ago. There are also a number of current projects we are acting on considering this evolving funding option.

Links to some of our recent credentials for income strip transactions are:

Bournemouth: Bournemouth University – QMPF

Cityheart Hereford: Cityheart Partnerships Limited – QMPF

More News…